Over the past decade, the field of oncology has been subjected to substantial changes in the way patients with cancer are being treated. We have departed from a “one-size-fits-all” treatment approach and entered an era with an increasing focus on precision medicine based on genomic variants (1).

In order to better understand cancer and to develop drugs to fight cancer, medical researchers have been studying genes and the changes in these genes for a very long time. The goal behind this research is to create therapies that disrupt various steps in cancer growth but cause minimal damage to normal cells.

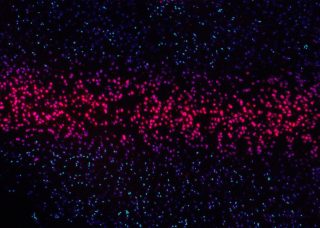

Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

These therapies are referred to as targeted drugs or targeted therapy. Researchers have noted that some types of cancers are frequently associated with specific genetic mutations. Not every cancer has a genetic source, but a significant percentage will. It is also noteworthy that cancers with these mutations usually have a more predictable response to certain drug treatments compared to cancers without these mutations (2).

Gene therapy the key to cancer treatment?

Gene expression is the process where the body makes specific proteins from the information contained within genes. Different tissues express different sets of genes based on their function in the body. Within the cell, information from genes is used to make a template for building ribonucleic acid (RNA). This RNA is processed to create the protein that is required by the cell. In patients with breast cancer, this is translated into multi-parameter gene expression tests (3).

Gene expression tests evaluate the RNA in a person’s tissue sample to determine which genes are actively making proteins. These are tests that evaluate the products (RNA) of specific groups of genes in the malignant (cancerous) tissue from the breast in order to determine which genes are making proteins within the tumour. This information can then be used to predict the outcome by estimating the risk of recurrence of the cancer. It is also used to guide treatment (4).

Breast cancer and gene mutations

Each breast cancer has an individual set of genetic mutations that distinguishes it from normal tissue. These mutations within the cancer cells and the related changes in the expression of those genes regulate how rapidly the cancer grows.

Each breast cancer has an individual set of genetic mutations that distinguishes it from normal tissue. These mutations within the cancer cells and the related changes in the expression of those genes regulate how rapidly the cancer grows.

This also determines the likelihood of metastasis. It will determine whether its growth is supported by the hormones oestrogen and/or progesterone or whether it over-expresses certain proteins such as HER2. Ultimately, it influences how responsive the cancer will be to various treatment modalities.

Rather than evaluating a single gene, multiparameter gene expression tests analyze the RNA of multiple genes within a cancer at the same time. The result is a pattern of gene expression that is consolidated into a score and/or profile. This information is then used to help predict the likely behavior of the cancer and its response to the available treatment options.

These tests are relatively new, but their use is increasing as they become more affordable and available. Their use is aimed ultimately, at developing a personalized approach to patient care and breast cancer therapy.

How far are we?

In Cape Town, a comprehensive breast centre has been using molecular genetic profiling and testing for more than 15 years. They have documented the clinical progress of more than 300 patients diagnosed with breast cancer who have undergone molecular genetic profiling of their breast tumours.

The tumours were selected for molecular genetic profiling as part of the normal consultative process. Patients were older than 18 years with histopathological (microscopic examination of tissue in order to study the manifestations of the disease) confirmation of early breast cancer (the tumour was less than 5 cm across and had spread to a maximum of 3 axillary lymph nodes). In these patients, it is often not clear whether they will benefit from the addition of chemotherapy after their surgical management. Oncologists are inclined to rather give chemotherapy than omit it, to avoid compromising patient outcomes.

Africa Studio/Shutterstock

Chemotherapy and genes

In these patients, chemotherapy was recommended if the molecular genetic profile indicated a high-risk of relapse; conversely, chemotherapy was not recommended if the molecular genetic profile indicated a low risk of relapse. Each patient was consulted by a team consisting of a surgical, medical, and radiation oncologist. Once a decision on further treatment was taken, established protocols were followed.

These patients have been monitored and followed up, for over more than a decade, to determine whether an individual treatment plan based on the genetic markers in the tumour has resulted in a better outcome than the standard treatment.

Out of more than 300 patients, half were low risk based on the outcome of the molecular genetic profiling; all have survived without relapse despite not having had chemotherapy. Conversely, out of the high-risk group, despite receiving chemotherapy, 3 patients have relapsed indicating that the risk assessment with molecular genetic profiling was accurate.

The major outcome of the study, however, was that more than half of the patients that ordinarily would have received chemotherapy could safely be spared chemotherapy with all its feared side effects without compromising the outcome. Also, a few patients who ordinarily would not have received chemotherapy were identified as having high-risk tumours and receiving chemotherapy, a potentially life-saving addition to their treatment.

What does this mean?

Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

These outcomes are in accordance with experience in the best overseas cancer centres. They confirm that molecular genetic testing can reduce the number of individuals who undergo chemotherapy. It can also save lives due to a more aggressive treatment regime being prescribed for individuals who at first diagnosis would be seen as low risk.

It gives medical professionals a new level of information from which to determine prognosis and treatment options. Ultimately, it allows for a more individualised approach to cancer prognosis and treatment.

![women [longevity live]](https://longevitylive.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/photo-of-women-walking-down-the-street-1116984-100x100.jpg)