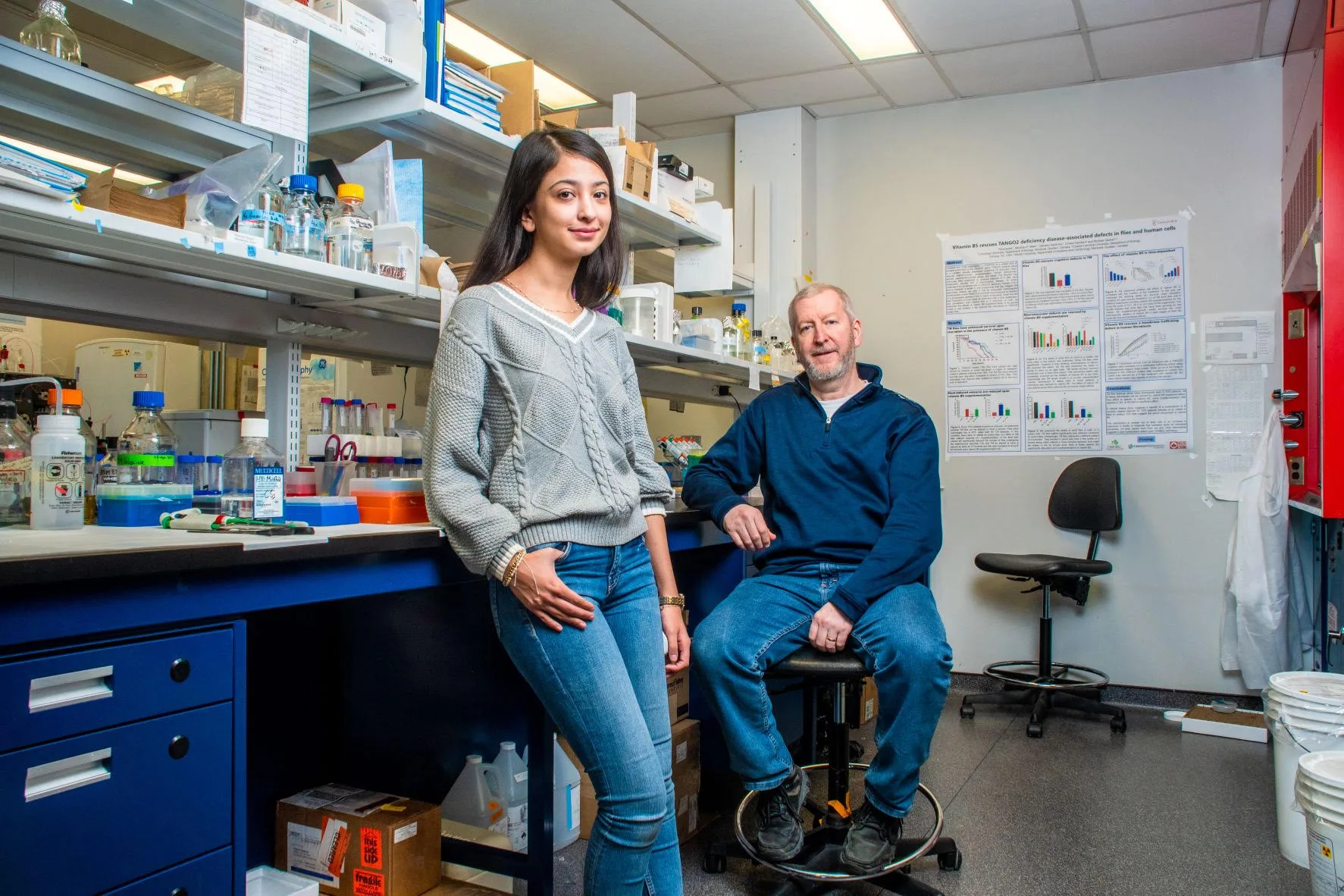

Research News from Montreal, August 8, 2023- A simple vitamin could successfully treat a rare but potentially fatal genetic disease, according to new research led by a Concordia undergraduate student. Undergrad Paria Asadi. She found immediate benefits in fruit flies with TANGO2 deficiency disease. Her research suggests vitamin B5 could potentially be therapeutic for TDD

Vitamin B5 can mitigate life-threatening effects

In a paper published in the Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease, the authors describe how vitamin B5 can mitigate the life-altering and life-threatening effects related to mutations in the Transport and Golgi Organization 2 (TANGO2) gene in Drosophila melanogaster—fruit flies. Flies with the mutation exhibited symptoms commonly associated with TANGO2 deficiency disease (TDD): they died of starvation almost twice as fast as those without it, had difficulties moving and learning, and had a neuromuscular defect that manifested as spasms when exposed to high temperatures.

However, when flies with the mutation were supplemented with vitamin B5, these symptoms quickly improved or, in some cases, disappeared.

“TDD is a very rare disease, but some clinicians noticed that phenotypes in patients with TDD resembled phenotypes in individuals who can’t metabolize lipids very well,” says Michael Sacher, a professor from the Department of Biology in the Faculty of Arts and Science and the paper’s supervising author. Lipids are fatty compounds that perform several important functions, including moving and storing energy and producing hormones. They are generally activated by bonding with the coenzyme A molecule, which needs vitamin B5 to be produced.

“Since TDD is a lipid metabolism problem, we thought that if we just boosted production of coenzyme A, we would see some sort of effect on the fruit flies,” Sacher continues. “And that was exactly the case.”Paria Asadi: “Just knowing how meaningful the research we are doing is for the lives of TANGO2 deficiency disease–affected families was a turning point in my life.”

Clear and rapid improvements

The paper’s lead author is Paria Asadi, who expects to complete her B.Sc. in fall 2023. She designed and conducted a series of assays to record the differences between control and experimental groups of fruit flies. Asadi first studied the behavior of fruit flies with the mutation and noticed phenotypes consistent with TDD seen in humans: they died 50 percent faster if deprived of food, suggesting a metabolic defect; they exhibited ataxia, a neurodegenerative condition characterized by poor muscle control and abnormal movements, among other symptoms; they exhibited intellectual deficits during in a learning assay, in which the flies were slower to avoid exposure to the bitter taste of quinine than those without; and they were more susceptible to seizures when exposed to higher temperatures.

She then repeated these experiments on another line of fruit flies with the TDD mutation, but with vitamin B5 added to their food. The results were not only remarkable—they were also quick. “We saw that they had improved, in some cases to wild levels,” she says. “They did not have a very significant learning deficit or metabolic crises after starving. This shows that vitamin B5 can potentially be therapeutic for TDD patients.” Other types of B vitamins were also used in tests, but none led to rescues as pronounced as B5.

Any exposure to vitamin B5 is good exposure

The researchers noticed degrees of improvement even after very short exposure to vitamin B5. The longer the exposure, however, the more marked those improvements were. “We were seeing a time-dependent rescue,” Sacher says. “Presumably, that would hold for humans as well. Even if a neurodevelopmental delay has occurred, which unfortunately happens to children, we can at least try to prevent a potentially fatal metabolic crisis.”

Vitamin B5 research was a turning point

Asadi recalls presenting these findings at a TDD family conference in summer 2022 where she had a chance to talk to families affected by the disease.

“One of the mothers told me that since her child started taking multivitamins their lives had changed for the better. Just knowing how meaningful the research we are doing is for the lives of affected families was a turning point in my life,” she shares. “It made me realize how biological research at the molecular level can be impactful for so many people.”

Research team

The researchers recently received a one-year $50,000 (US) grant from the TANGO2 Research Foundation to continue their work. Concordia researchers Miroslav Milev and Djenann Saint-Dic and former Concordian Chiara Gamberi, now at Coastal Carolina University in the United States, co-authored the paper.

Study references

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the TANGO2 Research Foundation, the National Institute of Health and the IDeA Network for Biomedical Research Excellence.

More about Paria Asadi

Can you tell us about the research project you’re doing right now?

“After my first year at Concordia, I started emailing professors to ask if I could volunteer in their labs. One of the professors encouraged me to apply for the Concordia Undergraduate Student Research Awards program, so I applied in the summer of 2021 and then started my work at Dr. Michael Sacher’s laboratory.

When I joined Dr. Sacher’s laboratory, my knowledge and techniques were very minimal. The process of learning can be frustrating, but I was patient and continued to work. I started working on a disease called TANGO2 deficiency. It’s a mutated protein in humans that leads to a very complex disease phenotype. There is very little information about this protein, so our goal was to understand the function and localization of this protein and try to find therapeutics.

I started this research project two years ago, and now it’s the topic of my Honours thesis. Recently, a paper that I worked on with Dr. Sacher and his team was accepted into a journal. It’s a huge honour for me to know that I started from scratch, but now I have my first authorship on a paper published in the Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease.” – Extract from Concordia University.

![women [longevity live]](https://longevitylive.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/photo-of-women-walking-down-the-street-1116984-100x100.jpg)