A treatment program designed for peanut-allergic preschoolers and babies has proven effective at helping children overcome life-threatening food allergies, says an allergist from a top American hospital, Cleveland Clinic. She describes it as a life-changing – and perhaps life-saving – outcome.

Living with food allergies

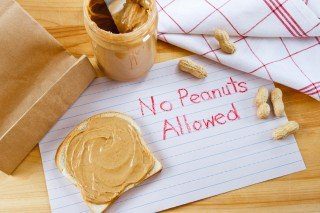

Sandra Hong, MD, Director of the Food Allergy Center of Excellence at Cleveland Clinic, explains that a food allergy is a condition where the body’s immune system identifies food (such as peanuts) as harmful. The immune system then launches into attack mode and releases antibodies to combat the threat. The reaction can lead to hives, vomiting, or – in worst-case scenarios – constriction of airways and even death. ![peanut butter spread [longevity live]](https://longevitylive.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/peanut-388785_640-320x213.jpg)

While data is not available on prevalence worldwide in the U.S., currently more than 1 million children living with a peanut allergy, with the knowledge that one bite of the food could be deadly. “For us to be able to help someone move past that — it’s the most rewarding part of our careers,” says Dr. Hong.

That optimism reflects the findings so far from an early peanut oral immunotherapy (EPOIT) treatment program developed at the Cleveland Clinic.

In the program, children aged four and younger who are allergic to peanuts built a tolerance to peanuts by ingesting minuscule amounts of the food in a step-by-step, allergist-supervised process. Doses have increased gradually over many months.

This approach represents a reversal from clinical guidelines shared by allergists a decade ago. Looking at the older approach, Dr. Hong explains that as food allergy numbers began spiking in the U.S. in the 1990s, doctors recommended that allergenic foods such as milk, eggs, and peanuts be removed from the diets of children with a high risk of allergies.

That thinking began to change, though, as research showed that eliminating specific foods did not slow the development of food allergies.

Alexandr Vorobev/Shutterstock

Then came the groundbreaking Learning Early About Peanut (LEAP) allergy study in 2015. The study found that the development of peanut allergies decreased in at-risk children with an early introduction of the food.

“It was completely the opposite of what we had believed,” notes Dr. Hong.

Next steps in peanut allergy treatments

Ongoing treatment programs aim to refine the treatment process that grew from the LEAP study, says Dr. Hong. More than 50 children with an identified peanut allergy are in the program.

The minimal goal is to help these children achieve at least “bite-proof” tolerance to peanuts, meaning they can consume nearly two peanut kernels without a reaction, says Dr. Hong. It protects against an accidental nibble of food with peanuts, leading to a health emergency.

Many participants, however, see their immune system responses change so much that they can eat peanut products, says Dr. Hong.

The key is the age of the participants, as reactions to food allergens typically are less severe in early childhood. “Their immune system is so malleable, so flexible, that they can tolerate it,” notes Dr. Hong. “There is this narrow window where we can do this.”

A series of peanut doses given to participants involved tiny amounts of food. In the initial treatment cycle, for example, the daily dose is 8 milligrams of peanut protein.

Small increases follow every two weeks if there are no setbacks, says Dr. Hong. The process takes at least four to six months, with maintenance dosing then continuing for at least a year.

Every uptick in peanut butter dosage takes place in an allergist’s office in case there’s a reaction. “This is not something you do at home,” stresses Dr. Hong. The child is monitored for an hour after the higher dose.

Of the children in the Cleveland Clinic program, more than 80% now possess “bite-proof” tolerance or are building up to that level.

The future outlook for children with peanut allergies

Currently, one in five children with a peanut allergy outgrows the condition before adulthood. Dr. Hong says advances in treatment could reverse those numbers, with as many as four in five children leaving their peanut worries behind.

Dr. Hong believes the number of children with severe peanut allergies will soon begin to decline. “We’re moving toward a cure,” she says, “and a lot less worry for families.”

![women [longevity live]](https://longevitylive.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/photo-of-women-walking-down-the-street-1116984-100x100.jpg)